johndoe@gmail.com

Are you sure you want to reset the form?

Your mail has been sent successfully

Are you sure you want to remove the alert?

Your session is about to expire! You will be logged out in

Do you wish to stay logged in?

Evolving alongside live-action filmmaking, animation has continually reinvented itself through artistic innovation and technological advances, from hand-drawn shorts to today’s CGI blockbusters. This new essay and accompanying free-to-view content from Screen Studies unpacks the history of animation, charting its journey through shifting styles, tools, and techniques.

Animation existed long before cinema. In the seventeenth century, early devices such as the magic lantern featured images painted onto glass and then projected using light and lenses to create basic moving visuals. Later inventions such as the zoetrope, designed in 1834, created the illusion of movement by spinning a series of images and allowing viewers to see them one at a time through small slits. These optical toys, while viewed by the Victorian public as entertaining novelties, also demonstrated a fundamental principle of animation and filmmaking in general: that still images could create the illusion of movement through the phenomenon known as the persistence of vision. As Dan Torre observes in this chapter of Animation – Process, Cognition and Actuality, ‘the animation process readily encourages the separation of the animation frame into multiple independent layers,’ a technique that defined traditional animation and can be ‘traced back to some of the pre-cinematic animation devices.' These early experiments laid the technical and artistic foundations for the animation techniques later refined by pioneers like Walt Disney.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, developments in photographic technologies such as readily available film stock and early film cameras like the Kinetograph, allowed artists to formally experiment with the emerging medium. In 1908, Émile Cohl created one of the first fully animated films, Fantasmagorie, by painstakingly drawing 700 individual frames to create a short that runs less than two minutes.

A few years later in Russia, Ladislas Starewicz created pioneering stop-motion films, a technique involving animating objects by photographing them one frame at a time as they are moved in tiny increments. In his 1912 film, The Cameraman’s Revenge, Starewicz used dead insects in the place of puppets, moving them frame by frame to explore adult themes of infidelity and voyeurism. In this chapter, Seeing in Dreams – The Shifting Landscapes of Drawn Animation, Bryan Hawkins notes that ‘Starewicz’s innovations can stand as an introduction to and example of animations’ innovatory forms as it draws upon and invents its emergent practices.’

Building on these early experiments, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) by Lotte Reiniger is the oldest feature-length animated film that survives today. Made using delicate paper cut-outs and backlit silhouette animation, it was technically and artistically ground-breaking. Reiniger’s innovative style helped to elevate animation as a serious art form, paving the way for the rise of major studios like Disney.

Founded in 1923, Disney has played a central role in shaping mainstream animation, popularising character-driven storytelling and innovative new techniques in animation. The studio’s preferred method of animation during the twentieth century was a process called cel animation, a technique where characters are hand-drawn and coloured on transparent sheets that are then layered over static backgrounds. This allowed for smoother movement and scenes of greater complexity. As Chris Pallant explains in this chapter from his book Demystifying Disney: A History of Disney Feature Animation, ‘Disney pursued an industrialized model of cartoon production’. Embracing the Hollywood studio system, the company employed hundreds of animators to meet the demands of high quality, large-scale animated filmmaking, creating some of the most iconic and successful animated films in history.

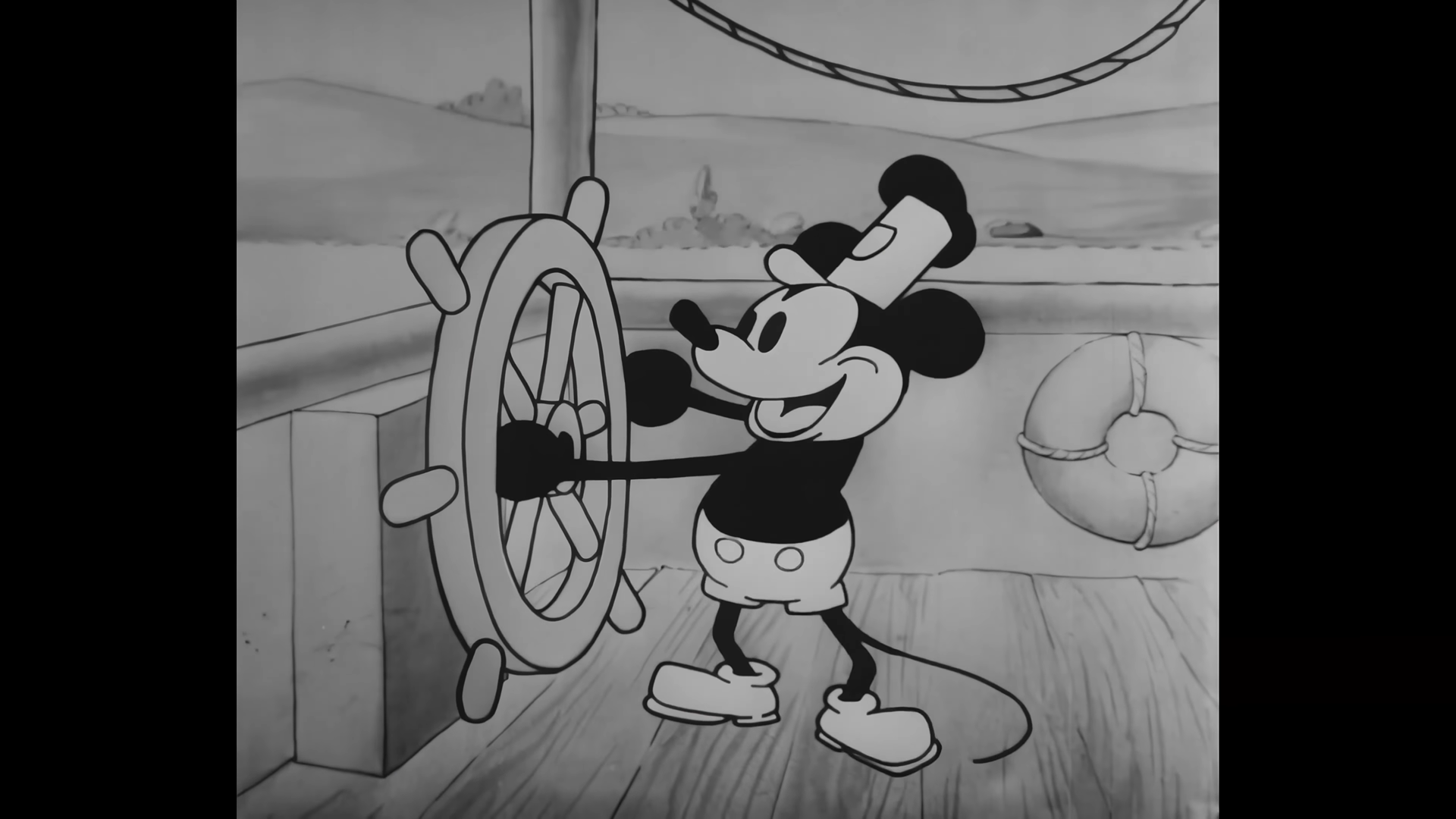

After Steamboat Willie (1928) the first animated short with fully synchronized sound, Disney’s defining moment came in 1937 with the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Eric Smoodin comments in his BFI Film Classic on the film, that ‘Snow White marked a significant moment in American art and culture’. The first full-length cel-animated feature film, Snow White’s enormous success proved that animation could tell compelling stories and appeal to both children and adults, helping to establish the medium as a legitimate and profitable cinematic form. The film marked the beginning of Disney’s ‘Golden Age’, which saw the studio create a slew of classics such as Pinocchio (1940), Fantasia (1940) and Bambi (1942).

After wartime setbacks, Disney refined its storytelling formula, reaching a peak in the 1990s with Broadway-style musicals like Beauty and the Beast (1991) and The Lion King (1994). The studio later embraced CGI in the 2000s, leading to a revival marked by modern themes and global hits such as Frozen (2013) and Moana (2016) that continue to dominate Hollywood today.

Across the Atlantic, as Richard Neupert notes, ‘European animation was forged by small teams, independent niche studios, and state film schools rather than Hollywood-style studios’. Lacking access to the large-scale resources of Hollywood’s dream factory, European animation often pursued more intimate and experimental approaches. Drawing on existing movements within the visual arts, German artists like Hans Richter and Walter Ruttmann created Dadaist, avant-garde works in films like Rhythmus 21 (1921) and Lichtspiel Opus I (1923), using geometric shapes and surreal editing to explore the possibilities of animation beyond storytelling, helping to shape early experimental film.

Later, in the 1960s and 70s, independent European animation studios continued to reject Disney’s naturalistic style in favour of bold, stylized visuals and unconventional narratives. Films like The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine (1968) and René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet (1973) used surreal imagery and psychedelic soundtracks to create strange, dreamlike experiences that challenged traditional storytelling and expanded the possibilities of the medium.

This experimental tradition continued with filmmakers such as Jan Švankmajer, whose 1988 film Alice reimagined Lewis Carrol’s classic in nightmarish fashion. Far removed from Disney’s colourful, whimsical adaptation, Švankmajer used stop-motion and everyday objects to create a world of decay, violence, and psychological unease. Exploring the director’s process, William Verrone posits in this chapter from Adaptation and the Avant-Garde, that ‘Švankmajer believes animation [is] an essential tool for capturing the power of the imagination…in his films, one sees how objects have personalities of their own; his animation reveals the mysterious personalities existent in dormant objects’. Today, filmmakers continue to embrace stop-motion as a powerful tool with which to bring their visions to life. Recent feature-length productions such as Phil Tippett’s Mad God (2021), Adam Elliot’s Memoir of a Snail (2024), as well as Aardman Studios’ Wallace and Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl (directed by Merlin Crossingham and Nick Park, 2024), all demonstrate the continuing appeal of this meticulous craft.

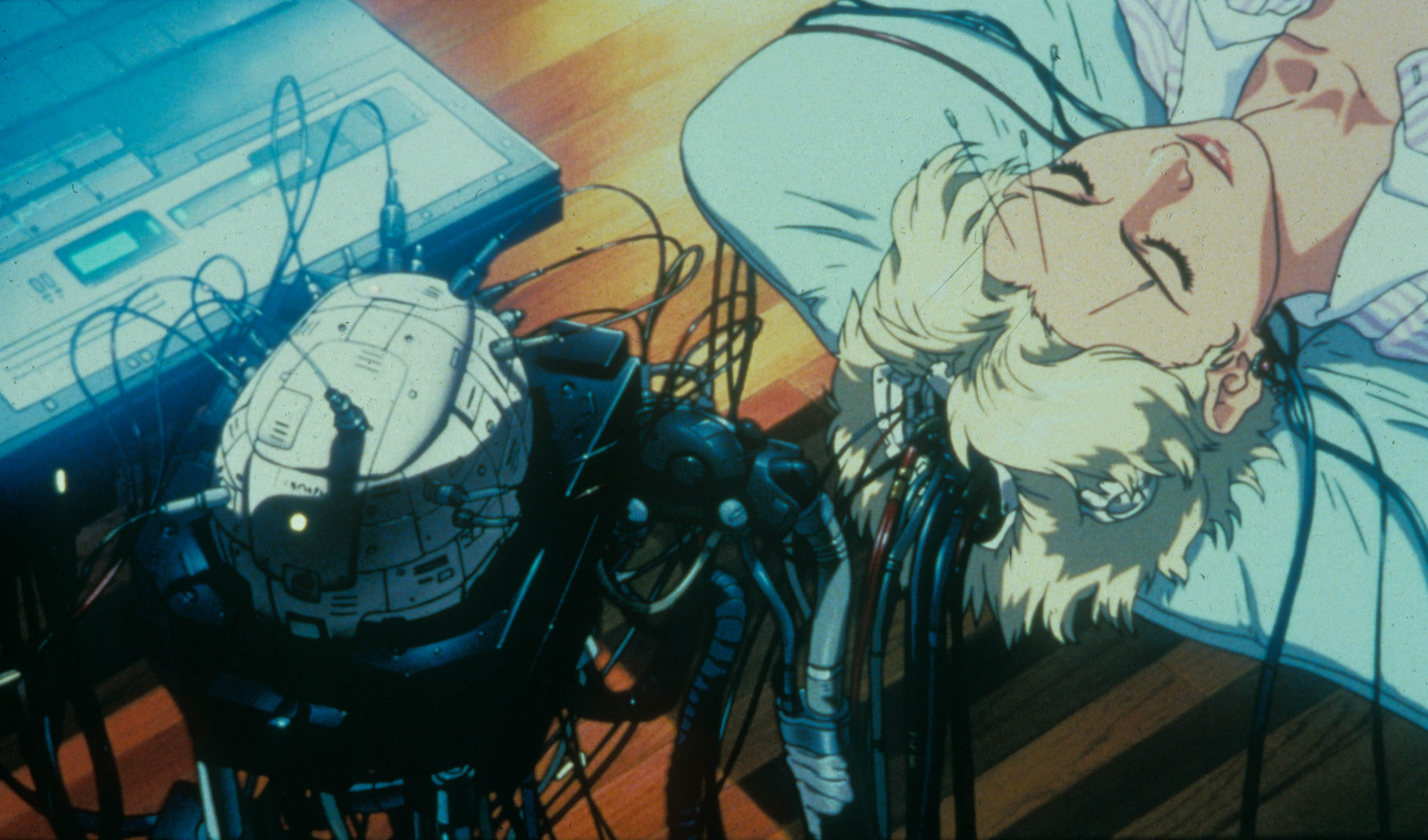

After the US, the largest producer of animated content is Japan, where the word ‘anime’ simply refers to any animated film or television. Anime is distinguishable from traditional American animation by its emphasis on detailed visuals rather than fluid movement. Anime also often uses animation ‘on threes,’ holding each frame for three beats, as seen in films like Ghost in the Shell (1995), Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995) and television shows such as Cowboy Bebop (1998). American animation typically animates on ones or twos for smoother motion. This technique gives anime its unique rhythm and visual style.

Starting in 1963 with Astro Boy, which many consider the first anime TV series and one of the earliest to reach international audiences, the ‘on threes’ technique was primarily a cost-cutting measure, and largely arose out of the need to meet tight budgets and weekly deadlines. American studios such as Hanna-Barbera Cartoons, who produced such hits as The Flintstones (1960 to 1966) and Scooby-Doo (1969 to 1976), employed similar techniques. Nichola Dobson comments in her chapter, ‘TV Animation and Genre’, this ‘transnational exchange of series between East and West, which started with Astro Boy, has seen an increased audience for…different forms and styles of animation and for different age groups. The growth in animated television generally…has seen a rise in innovative TV animation, for both children and adults.’ Of course, while a common style was established within Japan, artists continued to experiment and push the boundaries of the medium, blending traditional techniques with new technologies to create bold, genre-defying works.

While Disney were responsible for popularising feature-length animation in the West through fairy tales and musical fantasies, Studio Ghibli redefined the medium in Japan by crafting quiet, emotionally complex stories that elevated anime to a globally respected art form.

Founded in 1985 by Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and Toshio Suzuk, Ghibli ‘committed to producing works with greater detail and fluidity than the cost-cutting ‘limited animation’ that defined the look of so much anime,’ as Alex Dudok de Wit explains in this chapter of his book on the Ghibli classic Grave of the Fireflies (1988). A visionary director and animator, Miyazaki became the creative heart of Studio Ghibli, shaping its identity through richly imaginative worlds and complex characters. Melanie Chen explains in her chapter from Animated Landscapes, while today ‘the overwhelming majority of animated films made by Disney, DreamWorks and Pixar are predominantly made using computer-generated imagery, which features strong outlines and flat blocks of bright colour…Miyazaki’s anime films seem to be aligned more with the codes and conventions of painted and hand-drawn images.’ As CGI has become the dominant method of production in Western animation, Ghibli have continued to treat the medium as a fine art, handcrafting their films with meticulous attention to detail, texture, and movement that preserves the warmth and expressiveness of traditional animation.

While Ghibli carried forward the spirit of Disney’s Golden Age with hand-drawn artistry, Hollywood studios rapidly embraced CGI as their primary mode of animation with the rise of digital technology. This digital transition was cemented by the release of Toy Story in 1995, the first fully computer-animated feature film, which marked a turning point in animation history and set the standard for a new era of digital storytelling. Writing on the film’s impact in this chapter from Toy Story, Tom Kemper explains that the ‘film’s commercial and artistic success launched computer animation as an exciting new medium…that inspired more companies to invest in animated features, thereby contributing to what many considered a new golden age of animation’.

As digital animation tools have rapidly become more sophisticated as well as more accessible to filmmakers, digital animation today has increasingly seen widespread use across different genres and formats, from major studio productions to independent films, television, and online content. The winner of last year’s Oscar for best-animated feature film, Flow, written, directed, and largely animated by filmmaker Gints Zilbalodis, was made in Blender, a free and open-source software available to anyone with a computer. A Latvian, French, and Belgian co-production, the dialogue-free film follows a black cat navigating a precarious post-apocalyptic landscape in search of safety. With a budget of just $4 million, Flow stands in stark contrast to big studio animations such as Disney’s recent sequel, Inside Out 2, which had a production cost exceeding $200 million.

While independent filmmakers have explored the possibilities of animation, more traditional animation methods also continue to have a large presence within the industry. Major studios such as Pixar and Dreamworks, have increasingly moved away from purely CGI-animated films, now opting for productions that blend both older and modern aspects of animation. DreamWorks' The Wild Robot (2024), directed by Chris Sanders, blended hand-painted, 2D-inspired aesthetics with 3D animation, marking a bold return to the artistry of classic animation. Meanwhile, independent studios such as Aardman and Laika continue to show the enduring appeal and creative potential of other traditional techniques like stop-motion.

Writing in her chapter from The Animation Studies Reader, Lily Husbands explains the medium’s continuing appeal: ‘Animation as a technical process offers artists extraordinary potential for formal experimentation and expressive freedom. It has a remarkable capacity for imaginative visualization, and the diversity of experiences that can arise out of that creative potential is part of what makes animation such a fascinating object of study.’

Over the last century, animation has evolved from its simple roots into a diverse and dynamic art form that continues to combine technology and creativity, opening new possibilities for storytelling in the future.

Homepage banner image courtesy of Maximum Film / Alamy Stock Photo.